|

| Photo by Suzanne Currie |

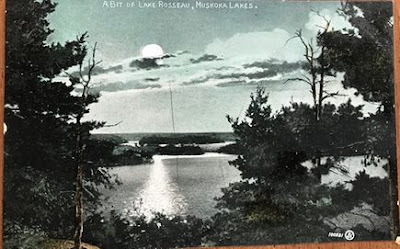

BRITISH HORROR WRITER WAS ENCHANTED BY THE BEAUTY OF LAKE ROUSSEAU CIRCA 1892

By Ted and Suzanne Currie

I have never once, even under the influence of a couple of lubricating drinks, entertained the idea of becoming a writer of horror stories. I admire the work of authors of horror stories and novels, but don’t have the creative juice or background to compose anything of the horror genre. I wish I did but I’m too long in the tooth, as they say, to change directions now. But I am intrigued about what British author, Algernon Blackwood found in the Muskoka lakeland, that may have inspired him to write several significant stories that may have had a root in the wilds of Canada, and potentially Lake Rosseau where the famed author resided for three months before the turn of the 1900’s. Two decades later nearby Tobin’s Island and the Muskoka Assembly at Wigwassan Lodge, would bring together dozens of internationally acclaimed writers for an annual retreat, of about ten consecutive summers, to discuss contemporary issues in literature at home and abroad. There were authors such as Sir Gilbert Parker, Marshall Saunders (author of Beautiful Joe), poets Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carmen and Wilson MacDonald. Earlier than this, indigenous poet Pauline Johnston paddled these same waters of Lake Rosseau and connecting Shadow River. Johnston was the author of the poem “The Song My Paddle Sings.” Obviously, Lake Rosseau offered its mystique to writers and artists, and in the case of Blackwood, the experience in Muskoka remained a fond memory until the end of his life.

A couple of venerable old crows are perched in a scraggly pine at the water’s edge, watching and cackling as the sound of the paddle, dripping with dark water current, can be heard from just around the rock face of the island. The canoe glides along the rocky shoreline, fading in and out of the small inlets and coves, disappearing into the bosom of evergreens, growing from small pockets of soil cradled by the craggy landscape. There is a gentle rocking of the watercraft, as the lone canoeist paddles in and out of the shadows of the late afternoon. The lapping of small waves against the rocks makes a rhythmic gurgling sound, as the action turns down upon the sand bottom, re-sculpting the environs as it has done since the beginning of time.

The color of the water in this stirring channel changes with the positioning of the sun toward its setting in a few hours, in this clime of late October. It can appear silver one moment, dark and precarious when cloud cover distorts the sun glow temporarily. It will appear quite different, in reflection, when the sun gives up on this day, and after the orange and red tint upon the rippling tide, the water will soon appear black and cold, despite the fact the weather betrays this attitude. It is still quite warm for this time of the autumn, the trees having avoided heavy frost to this point. The trails of colored, fallen leaves smooth over the water at this time of day, as if they are floating down through the sky. There are many optical illusions in this haunted lakeland, and it is not surprising that British Horror writer Algernon Blackwood found his stay on this Muskoka lake so remarkable, such that he never forgot his five month camping experience on Wistowe Island for the balance of his life, which, as a matter of interest, extended into his 86th year.

The white canoe is only a dot on the waterfront at this point, as the channel opens into the wider Lake Rosseau near the Village of Windermere. The old sun is not long for this day, and the encroachment of heavy clouds suggests the voyeur might soon wish to seek cover from the coming rain. There is the eerie shrill of a loon, still residing in this lakeland, and the sound of wheezing wind rising from the west, singing through the border evergreens, in a most beautiful and haunting refrain, as the gentle first stage of inclement weather pushes across this storied lake. It was the kind of scene that played out for the young Algernon Blackwood, standing out on the shore, in the embrace of autumn twilight, thinking about the spirits dwelling within. The spirits identified by poets and philosophers who attended the Muskoka Assembly of Writers, on Tobin's Island, in the 1920's, almost three decades after Blackwood's initial stay on Wistowe Island.

"By far the strongest influence in my life, however, was nature;" asserted Algernon Blackwood in his 1923 biography, "Episodes Before Thirty". Adding, "it betrayed itself early, growing in intensity with every year. Bringing comfort, companionship, inspiration, joy, the spell of Nature has remained dominant, a truly magical spell. Always immense and potent, the years have strengthened it. The early feeling that everything was alive, a dime sense that some kind of consciousness struggled through every form, even that a sort of inarticulate communication with this 'other life' was possible, could I but discover the way - these moods coloured its opening wonder. Nature, at any rate, produced effects in me that only something living could produce; though not till I read Fechner's 'Zend-Avesta,' and later still, Jame's 'Pluralistic Universe,' and Dr. R.M. Bucke's 'Cosmic Consciousness,' did a possible meaning come to shape my emotional disorder. Fairy tales, in the meanwhile bored me. Real facts were what I sought. That these existed, that I had once known them but had now forgotten them, was thus an early imaginative conviction."

The author recalls that "This tendency showed itself even in childhood. We had left the manor house, Crayford, and now lived in a delightful house at Shorthands, in those days semi-country. It was the time of my horrible private schools - I went to four or five - but the holidays afforded opportunities.

"I was a dreamy boy," writes Blackwood, "frequently in tears about nothing except a vague horror of the practical world, full of wild fancies and imagination, and a great believer in ghosts, communing with spirits and dealings with charms and amulets, which latter I invented and consecrated myself by the dozen. This was long before I had read a single book. I loved to climb out of the windows at night with a ladder, and creep among the shadows of the kitchen garden, past the rose trees and under the fruit-tree wall, and so on to the pond where I could launch the boat and practice my incantations in the very middle among the floating weeds that covered the surface in great yellow-green patches. Trees grew closely round the banks, and even on clear nights the stars could hardly piece through, and all sorts of beings watched me silently from the shore, crowding among the tree stems, and whispering to themselves about what I was doing.

"I cannot say I ever believed actually that my spells would produce any results, but it pleased and thrilled me to think that they might do so; that the scum of weeds, might slowly part to sow the face of a water-nixie, or that the forms hovering on the banks might flit across to me, and let me see their outline against the stars. On returning from these nightly expeditions to the pond, the sight of the old country-house against the sky always excited me strangely. Three cedars towering aloft with their great funereal branches, and I thought of all the people asleep in their silent rooms, and wondered how they could be so dull and unenterprising, when out here they could see these sweeping branches and hear the wind sighing so beautifully among the needles. These people, it seemed to me at such moments, belonged to a different race. I had nothing in common with them. Night and stars and trees and wind and rain were the things I had to do with and wanted. They were alive and personal, stirring my depths within, full of messages and meanings, whereas my parents and sisters and brother, all indoors and asleep, were mere accidents, and apart from my real life and self. My friend the under-gardener always took the ladder away early in the morning."

Blackwood adds to his biography, noting, "Sometimes an elder sister accompanied me on these excursions. She, too, loved mystery, and the peopled darkness, but she was also practical. On returning to her room in the early morning we always found eggs ready to boil, cake and cold plum-pudding perhaps, or some such satisfying morsels to fill the void. She was always wonderful to me in those days. Very handsome, dark, with glowing eyes, and a keen interest in the undertaking, she came down the ladder and stepped along the garden paths more like a fairy being than a mortal, and I always enjoyed the event twice as much when she accompanied me. In the day-time she faded back into the dull elder sister and seemed a different person altogether. I never reconcile the two."

In his most profound declaration, about his spiritual connection with nature, Blackwood writes, "This childish manifestation of an overpowering passion changed later, in form, of course, but not essentially much in spirit. Forests, mountains, desolate places, especially perhaps open spaces like the prairies or the desert, but even, too, the simple fields, the lanes and little hills, offered an actual sense of companionship no human intercourse could possibly provide. In times of trouble, as equally in times of joy, it was to nature I ever turned instinctively. In those moments of deepest feeling when individuals must necessarily be alone, yet stand at the same time in most urgent need of understanding companionship, it was nature and nature only that could comfort me. When the cable came, suddenly announcing my father's death, I ran straight into the woods....This fall sounded above all other calls, music coming so far behind it as to seem an 'also ran'. Even in those few, rare times of later life, when I fancied myself in love, this spell would operate - a sound of rain, a certain touch of colour in the sky, the scent of a wood-fire smoke, the lovely cry of some singing wind against the walls or window - and the human appeal would fade in me, or, at least, its transitory character becomes pitifully revealed. The strange sense of a oneness with nature was an imperious and royal spell that over-mastered all other spells, nor can the hind of comedy lessen its reality. Its religious origin appears, perhaps, in the fact that sometimes, during its fullest manifestation, a desire stirred in me to leave a practical, utilitarian world I loathed, and become - a monk!"

One can imagine, in this light, the silhouette of the young Mr. Blackwood, standing out along the shore of Wistowe Island, after sunset, admiring the vast embrace of the nature he so adored. What did he perceive or see of this 1890's scene, in a still pioneering era region, that enforced his opinion, nature abounded with spiritual energy, compelling him to be its interpreter. When he was engaged in this five month retreat on this island in Lake Rosseau, he hadn't given much thought to engaging himself as a writer, though it is known he jotted-down stories the natural environs, at the time of a particular vigil, inspired him in the creative sense. Which, according to his biography, were filed away for some later posterity. It fact, a friend of his, borrowed some of these early stories, and without Blackwood's permission, gave the folio to a publisher for consideration. He was therefore, quite shocked when he got a letter from this same publisher, wishing to talk further about his company's willingness to put them in book form, for the reading public's benefit. He agreed that it was a financially interesting development, being still of modest income, to have such work, he originally thought unworthy of a publisher's attention, on the bookshelves of England. The rest, as they say, is history.

Please join us tomorrow, for part four of our series of articles, on the relationship between Muskoka and internationally acclaimed horror writer, Algernon Blackwood.